PUBLICATIONS: Heritage Highlights

Modern textile printing:

The lean years, 1930 - 1940

Article by Larisa Sarkadi

And that gent today… You gave a cent, today…

Once had several chateaux… Anything goes…

Cole Porter

The consequences of that seemingly local event, the Wall Street Stock Market Crash of 1929 in New York, spread far and wide among the increasingly interdependent economies of the industrialised world.

The ensuing economic depression affected all levels of enterprises, from large corporations laying off their workforce, to a local grocer, whose customers could no longer afford the basic necessities. By 1931, economic depression had reached France and also Britain, with its industrial north hit the hardest. The south of Britain fared somewhat better, with the influx of cheap labour from the north creating a construction boom. Due to its heavy reliance on trade in raw materials and agricultural produce, Australia felt the effects of this depression even earlier than European economies. By 1934, when Cole Porter penned the lyrics above for his musical “Anything Goes”, he was only half jesting. Worldwide, during the worst years of the Great Depression, 1933-1934, over a quarter of the adult population was unemployed or under-employed.

In line with other industries, textile manufacturing was forced to decrease production. Such was the case with the Calico Printers’ Association (CPA) in the UK. At the height of textile production, just over a decade previously, CPA had 29 printing workshops. By the end of the 1930s, their number had fallen to 11. In Austria, after three exceptionally creative decades during which Wiener Werkstatte produced thousands of original fabric designs, the collective closed its doors in 1932.

Reflecting the prevailing mood, textile decoration changed from the spirit of optimism of the 1920s to patterns in subdued, earthy colours. Brash, modern styles were out of favour with the buying public, as tastes returned to restraint in appearance. In the 1930s, projects involving avant-garde interior decorations were commissioned mainly by large corporations for the construction of cinema chains, hotels and ocean liners.

Under the growing influence of Bauhaus principles, the trend away from profuse ornamentation had commenced earlier, as a backlash to the stylistic excesses of Art Deco. Interior decorators were increasingly turning to textural effects, rather than surface decoration, in their choice of furnishing fabrics.

The cost of reproducing a printed pattern was lower than mechanical weaving; hence textile manufacturers were producing printed yardage, imitating woven texture. These textiles were marketed to an individual consumer wishing to update the home interior by using furnishing fabric with a woven appearance. In France by the mid-1930s, the trend moved away from abstract geometric patterns, to be replaced by designs featuring curves and even neoclassical revivals.

To cut costs, some manufacturers produced textiles with an undyed background, the number of colours used in a design being limited to six. In the period between 1930 and 1940 the scarcity of raw materials was compensated for by the inventiveness of designers. This inventiveness was one of the criteria of a design competition for master fabrics announced by the De Angeli Frua textile firm in Italy in 1933. The other criteria were originality of design and production efficiency. The winning entry, by the industrial and graphic designer Marcello Nizzoli, was pronounced “extremely suitable for printed fabrics”.

Technological innovations in Europe during the 1930s included the development of a warp-printing technique which involved printing a design on the warp (the length-wise running) threads prior to weaving. The resulting fabrics showed added depth of colours within artistically blurred patterns. Screen printing methods increasingly replaced block-and-roller printing as the most cost-effective and flexible way of producing short fabric runs. Small-sized, sparsely-placed floral patterns better suited the changed fashion style favouring figure-hugging dresses. Facing decreased demand, the fashion industry turned to less expensive synthetic fabrics, such as rayon, instead of silk. By the middle of the decade, more than 80% of dress fabrics were made from rayon. In the United States of America, the development of synthetic fibres continued with the invention of nylon in 1938.

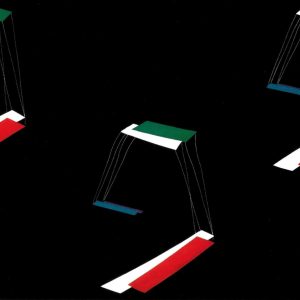

Designers of modernist interiors increasingly preferred fabrics in neutral shades of beige, terracotta-red and greyish-green, instead of pure primary colours. To meet these requirements,textile printing workshops softened primary colour dyes by the addition of black or white. Very few textile manufacturers risked going against this trend, with rare exceptions such as Arthur Sanderson’s printing workshops. In the early 1930s this firm produced a number of roller-printed patterns on cotton in vivid colours which represented a late blooming of Art Deco style in Britain. Another exception, the Calico Printers’ Association, was still producing strikingly graphic, Constructivist-inspired designs in yellow and red colours in the mid-1930s.

Inspired by artistic advances made earlier in France, many modernist designers in Britain in the 1930s created outstanding examples of screen-printed fabrics. Besides the above-mentioned textile printers, such firms as Alan Walton Textiles, Edinburgh Weavers and William Foxton also adapted their designs to meet an increasing consumer demand for a contemporary look. By the end of the 1930s, British dress fabrics, in their quality and innovative pattern range, were as good as the French-made textiles.

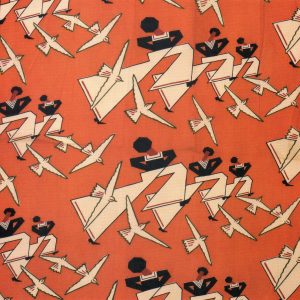

In Soviet Russia, multi-talented graphic artists such as Varvara Stepanova and Maria Anufrieva continued to produce extraordinary textile designs in the Constructivist style. Based on a precise grid of repeating geometric outlines, their brightly-coloured patterns praised the joys of factory work and sporting activities. By the mid-1930s, however, in an unexpected parallel with the capitalist West, the ruling government’s taste became more conservative. Such bold designs were deemed jarring with the new (more demure) ideal of femininity, and realistically-drawn floral motifs depicting roses, poppies and carnations became popular again.

In Australia, the race to replace printed textile imports with local products commenced in the late 1920s. After the interruption caused by the Great Depression, by the mid-1930s, with the economy on its way to recovery, textile designers continued their work on the development of local, unique lines. Such artists as Michael O’Connell (active as a designer and educator in Australia during 1929-1937), Margo Lewers and Frances Burke created strikingly modern patterns based on native flora and fauna, and often inspired by Aboriginal paintings. Produced by using woodblock and linocut techniques, their designs were printed mainly on linen and cotton for use as furnishing fabrics. In 1937 Frances Burke founded the very first registered screen-printing workshop in Australia. Trading as Burway Prints and based in Melbourne, the firm produced and retailed screen-printed cotton fabrics with stylised representation of Australian themes

The end of the decade also saw the emergence of other unique regional lines and the establishment of textile printing facilities elsewhere. In Hawaii small-scale printing workshops were producing exotically-coloured fabrics on the main island from the early 1930s. Typical designs represented a fusion of bark cloth patterns of the South Pacific and the Orient – neighbours along maritime trading routes – as well as native flora of the Hawaiian Islands. The most commonly used fabric was cotton broadcloth brought from mainland US.

In about 1930, in one of the lectures delivered to the Architectural Students’ Society at the University of Melbourne, Michael O’Connell said: “Textile decoration is the most important art apart from the movies, in the world today”. Towards the end of the 1930s, however, in the depressed socio-economic conditions of that decade, textile design – that most “wearable” form of applied arts – had lost its cutting edge. In 1939, with Europe plunged into war yet again, the artistic merits of a fabric pattern were no longer relevant. As was the case during the First World War, demands placed on the textile printing industry by governments caused production to be narrowed down chiefly to camouflage prints.

______________________

Originally published in The News, Autumn 2017 edition (pdf).