West of the Blue Mountains and a two-hour drive from Sydney, the Lithgow Small Arms Factory is an intriguing time capsule.

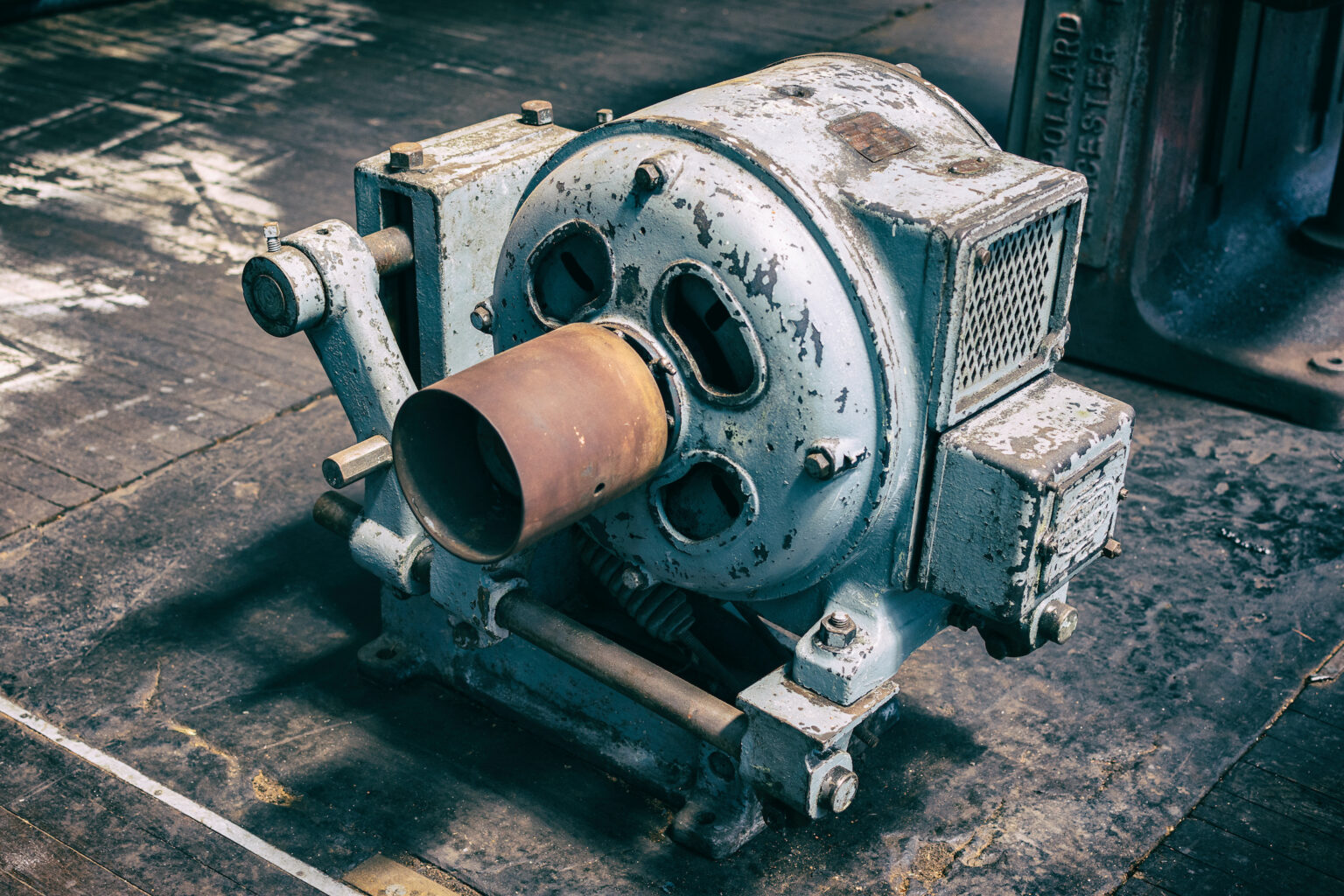

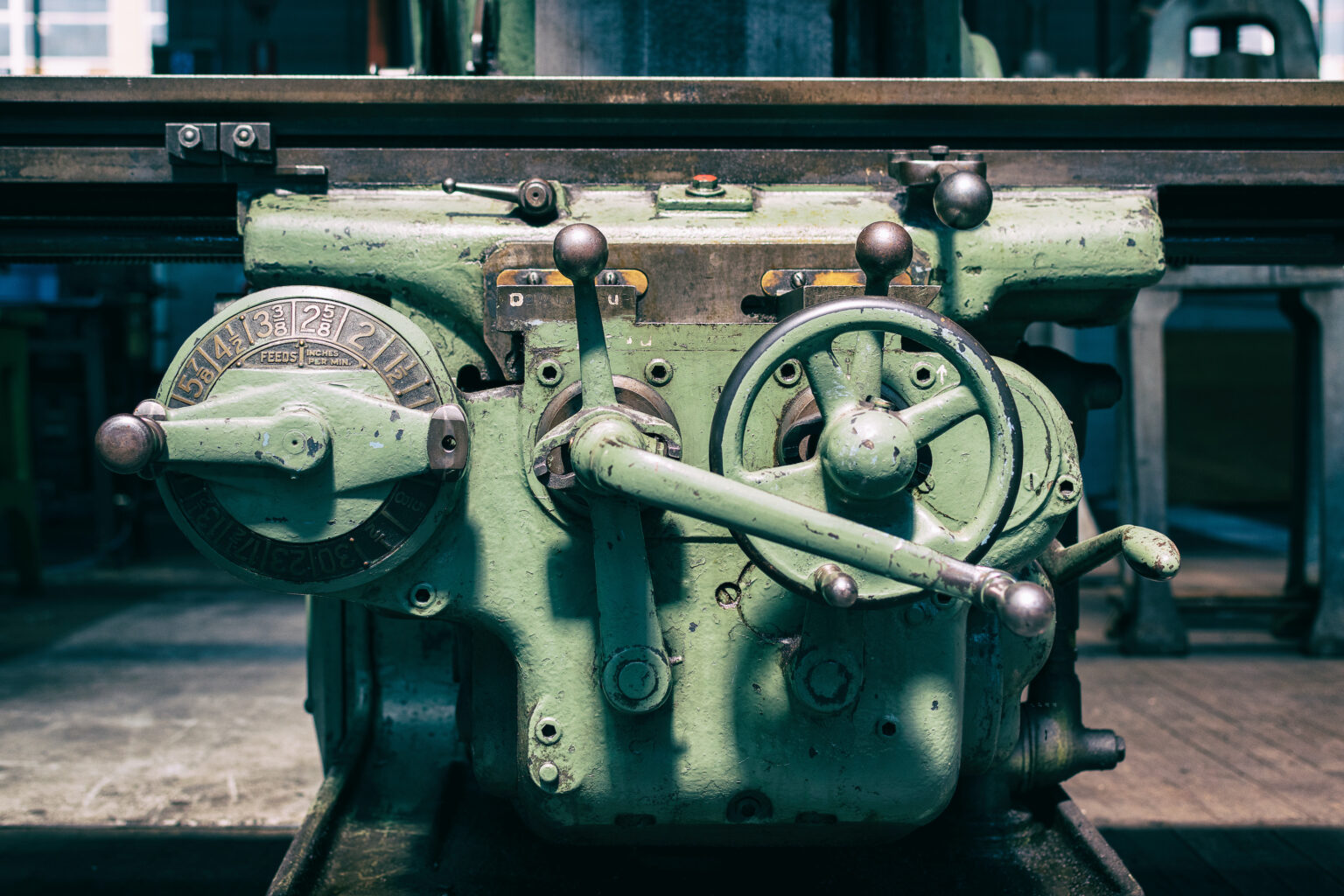

Opening for business on 8th June, 1912, the Lithgow Small Arms Factory and its many buildings are outstanding examples of 20th century industrial architecture. Several of the original Pratt & Whitney and other early machines have also survived.

But the cutting of the ribbon actually started way back in 1901. The Boer War made it apparent that Australia’s isolation from its armament source in the UK could lead to serious problems in future.

To remedy this, in 1907 the decision was made to establish a factory for the manufacture of small arms in Australia, a first for the Commonwealth.

Several sites had been put up as suitable locations for the new factory. In 1903 lobbying for Lithgow began in earnest. It had many advantages: Road and rail hubs, a thriving iron works and a remote location, over the Blue Mountains, well away from metropolitan Sydney.

When it officially opened in 1912, the factory floor covered approximately 8360 square metres. The factory had its own powerhouse, tool room and forge. Individual machines were driven by overhead pulleys with the shafting running the full length of the buildings. There were 340 machines, 11 forging hammers and 22 oil-fired furnaces.

Just in the nick of time.

That opening date of 1912 was fortuitous. Just two years later the Commonwealth was engaged in a World War. Soon, small arms production at the Lithgow site ramped up, producing British designed guns for soldiers in World War I and, from 1916, producing Australian-designed guns for diggers on the front.

When World War I was over, the Small Arms Factory went into decline, and Pratt and Whitney withdrew. However, it hung onto a small workforce during the inter-war years until another global conflict loomed in 1939.

There were soon 2,000 workers on site until 1942, at the peak of the conflict, when there were nearly 6,000, including, for the first time, hundreds of women. These women were immortalised by Heliodore (Dore) Hawthorne, a talented painter and art teacher, who lived in Lithgow during the war.

Some of her work is on display at the factory and it’s truly amazing: she drew many sketches of scenes from the factory and later produced a series of paintings entitled “Factory Folk” that reflected her commitment to social justice.

In the 1950s and 1960s the Modernist buildings that now fill the site were created and the site doubled as a high precision manufacturing facility. The factory served subsequent conflicts such as Korea and Vietnam, however, in recent decades production at the Small Arms Factory has contracted severely. The Small Arms Factory was privatised in the 1990s and since 2006 has operated as part of the Thales world-wide munitions supply group.

All roads lead to Lithgow.

I have been ‘over the hump’ of the Blue Mountains from Sydney more times than I can recall. Along the Great Western Highway or via the Bells Line of Road, our family have headed west on many trips and usually seem to return via Lithgow. Funny that.

I have been fascinated by all things military since I was a child and, now I have two sons who are equally fascinated, the ‘Lithgow Stopover’ is a firm favourite. We have been several times since I took up photography and I have enjoyed exploring the many nooks and crannies in the workshops and museum displays.

The factory that became a museum.

Situated on the existing Factory site, the museum is widely recognised for its comprehensive collection of modern firearms, and the sheer amount of hardware on display never fails to draw the breath. Pre-COVID, some of the guns could be picked up (don’t worry, they were safe and chained to a wall) but alas now, it’s just look but don’t touch.

Once for Australian Defence Industry eyes only, the historical importance of the collection of small arms, commercial products, machinery and tooling of the Small Arms Factory was recognised in 1995 – and the ADI agreed to gift the collection to Lithgow. The museum opened its doors to the public a year later.

Out in the workshops, the old machinery, some it the original Pratt and Whitney equipment, has beautiful typography emblazoned across it; the elegant curves of the old lathes and drills; the metallic colours still shining bright; the machines that seem to have human faces…all grist for my photographic mill.

You may wonder why there are no firearms in my images. There are a couple of reasons: First, there are so many on display I wouldn’t know where to start and second, I simply find the machines that make the guns so much more interesting.

Hope you enjoy exploring the place as much as we have. And will no doubt do so again soon…