RESOURCES: Heritage Highlights

One island.

A thousand and one stories.

Words and pictures by Peter Ogden

Cockatoo Island sits in the middle of a global city, yet many parts of it remain a relatively untouched treasure trove of history and atmosphere.

From an indigenous fishing base to a naval shipyard, via a penal colony and reform school…Cockatoo Island has seen it all.

Jumping on the ferry at the new Barangaroo Wharf, the journey to Cockatoo Island only lasts ten minutes but it took me back centuries. I hadn’t visited the island since discovering my love for photography, so I went this time with a very different set of eyes. My fondness for history was dialled up to 11 this time too, as I took my time going through each section of the island.

Prior to colonisation, the island served as a fishing and hunting base for the indigenous Eora People. Standing on the foreshore and looking around, trying to imagine the area before the Bridge and The Rocks was built, it’s easy to see why this would have been such a perfect place for that purpose.

Walking the island loop, heading clockwise from the ferry wharf, meant I landed at the industrial precinct first. The island was the site of one of Australia’s biggest shipyards, operating from 1857 for more than 130 years. The first of its two dry docks were built, understandably, by a convenient labour force – the convicts of the island’s penal colony.

Between 1847 and 1857, convicts dug out the Fitzroy Dock, Australia’s first dry dock. An estimated 42,000 cubic metres of rock was removed. The work must have been back-breaking – I can’t imagine they had too many excavators in those days.

Entering the engineering sheds, as big as aircraft hangars, day quickly becomes night, save for the pinpricks of sunlight that punch through the empty rivet holes. There is still lots of machinery left here, most of it rusting but still fascinating to wonder as to what purpose each served.

Shipbuilding began in earnest in 1870 but it wasn’t until 1913 that the island’s dock infrastructure was officially transferred and became the Naval Dockyard of the Royal Australian Navy. Good timing, it seems, with the First World War kicking off just a year later.

The destroyer HMAS Warrego, a ship originally built in the UK and sent Down Under in sections packed in crates, was the first naval ship launched at the site. During the First World War, the island was a hive of activity as ships were built, repaired and refitted. It’s hard to comprehend now, with the island feeling like a ghost town, that more than 4,000 workers toiled away day and night. The noise drifting across the water must have been interminable to the nearby residents. World War Two saw another spike in activity, as the shipyard become the main repair site in the South Pacific. The Cockatoo Docks & Engineering Company leased the facilities for many years after this…finally calling it a day in the early 90s.

Continuing the loop, the path leads from the darkness of the engineering sheds out into the light. I walk past docks, cranes, new cafes that have popped up in old sheds, the entrance to a tunnel that cuts through the sandstone heart of the island, past dry stores…all now showing signs of nature creeping up on them.

Traversing the back of the island reveals hints of the penal colony for the first time – sandstone blockhouses, buildings and grain stores sit on the high ground. In 1839 Cockatoo Island was chosen as the site of a new penal establishment, taking many transfers from Norfolk Island’s offshore penal colony. For the next 30 years the island was used as a convict prison, mainly for people who didn’t learn their lesson the first time – re-offenders. In 1869, the convicts were relocated to a jail in the city and the penal infrastructure transformed to an Industrial School for Girls. As you do. The mind boggles at the contrast…from penal colony to girls’ school.

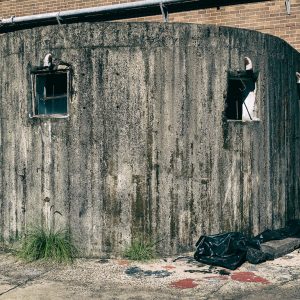

Heading back around the top of the island, I pass a large slipway, chimneys, a new campground and looming water towers. The machinery is no longer in working order and the flora of the island is reclaiming the land, creeping across tunnel entrances, up the side of towers, along the walls of WWII-era bunkers and bomb shelters. But it looks all the better for it…

As I sit waiting for my ferry back to the 21st Century, I look around and nod, wondering why it took UNESCO until 2010 to make Cockatoo Island a World Heritage Site.

Explore further:

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust – visit Cockatoo Island

References and acknowledgements:

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust – History of Cockatoo Island

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment – National Heritage Places

Heritage Council of Victoria – Industrial Heritage Case Studies